The Mystery of Tierra del Fuego (an herbarium whodunit) By Amy Rule

It started one day at the University of Arizona Herbarium when Linda Kennedy was examining some unmounted grass specimens from the John R. Reeder and Charlotte Goodding Reeder archive. Although the blades, rhizomes, and panicles were naked, just loosely and carefully folded inside yellowing pages, each one had a beautiful, formally printed label.

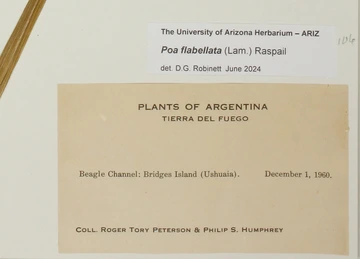

Such a label lends an aura of importance to any specimen, but what is missing from these labels?

We are given the basics -- a date (1960s), geographic location full of historic suggestions (Beagle Channel), and the title of the official collection (Flora of Tierra del Fuego). But there is no identification of the grasses. What jumps off the page is the two collectors’ names – Roger Tory Peterson and Philip Strong Humphrey -- surprising us in a botanical context.

Peterson (1908-1996) was a formally trained artist who changed the world of birding with his simple visual system for identifying birds in the wild. His 1939 A Field Guide to the Birds grouped similar-looking birds together and sold out in one week. Although not an ornithologist, he knew scientists and was on the staff of the Yale Peabody Museum in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The other collector on the grass label was Humphrey (1926-2009), a noted ornithologist, museum curator, and professor of zoology. After his doctoral thesis on sea ducks in 1955, he joined the Yale Peabody Museum (probably where he met Peterson) and then the Smithsonian Institution. Humphrey was awarded a Guggenheim Grant in 1959 leading to his study of birds in Argentina. Which brings us to Tierra del Fuego.

Darwin traveled there on the HMS Beagle during the hydrographic survey of 1826-1830. Specimens from that voyage are in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. There we also find botanical collections from the Wilkes Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842 and even Joseph Banks’ 1768 voyage with Captain Cook. The Smithsonian’s remarkable commitment to digital records makes it possible to see these plants from Tierra del Fuego hundreds of years after they were collected.

Three months of birding in Tierra del Fuego in late 1960 (described in Peterson’s book “All Things Reconsidered: my birding adventures” published in 2007) gave the two bird guys (Peterson and Humphrey) time to pay attention to plants along with everything else as they studied nests, feeding, and environment. Some of their plant specimens ended up in the Smithsonian collection. Rosaceae, for example. But grass specimens are lacking.

We have to speculate about why their 1960 Tierra del Fuego grasses went to Arizona instead of the Smithsonian.

The logical connection is Mary Agnes Chase (1899-1963), Curator of Grass at the National Herbarium and author of the influential First Book of Grasses (1962), which is still in print. Chase might have received Peterson’s and Humphrey’s specimens, realized the uniqueness of the samples, and reached out for the best expert determinations. Logically, she sent them to John (1914-2009) and Charlotte (1916-2009) Reeder, who she had known since the 1940s. These three grass experts and passionate students of all things grass-like were close colleagues from their days on the East Coast. Over the years, letters substituted for in-person consultations, so it is likely that the problematic Tierra del Fuego grasses were discussed by mail. Agnes kept her letters from Charlotte; they are available for research as Record Unit 229 (Division of Grasses) in the Smithsonian Archives. More of her papers are in the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation.

We don’t know if the Reeders worked on identifying the ten Peterson/Humphrey Tierra del Fuego specimens. They never recorded guesses or final determinations, possibly because at the time they lacked the extensive keys to the grasses available today. The Reeders were also living in New Haven at the time, so perhaps acquainted with Peterson and Humphrey, where John was a professor at Yale overseeing the herbarium for 20 years until 1968. Now all the major players in the story have passed on, but the Tierra del Fuego grasses will be identified, carefully mounted and digitized. Their story will be added to the ARIZ database.

These grasses with a long and interesting history are evidence of the long-standing tradition of global plant exchanges between collectors and herbaria. Thanks to this historic acceptance of a standard for information dispersal, herbaria have broadened accessibility to natural history collections, preserved the record of botanical networks, and protected the unique specimens of our human-created and wild landscapes.